The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), written by James Goldman from his stage play of the same name, with Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, Anthony Hopkins, John Castle, Nigel Terry, and Timothy Dalton. One must appreciate Beethoven to grasp the powers of this film, which reside principally in ensemble performance. O’Toole, as an English king visiting France and spending Easter with his stubborn and brilliantly contentious wife (Hepburn) and three sons (Hopkins, Castle, Terry), glows with vituperation, whines with loneliness, grimaces with intent, and fails in grand spectacular fashion to decide which of the pathetic offspring will wear his crown when he is dead. The serpentine French monarch Philippe (Dalton), visiting in order to light as many fuses as possible, does nothing to help the situation. For devotées of screen acting, it is a lesson to watch the young Hopkins, the young (and brilliantly polished) Castle, and the young Terry (who would play King Arthur for John Boorman in Excalibur) dash and pose in the shadows of the great Hepburn and the great O’Toole; every day on the set was an education for them, no doubt. Hepburn’s Parkinson’s is occasionally evident, a pointer to the fact that she worked against huge odds to bring off this stellar performance with its continual reversals and complex contradictions: she adores Henry, but she will do anything to destroy him. As for O’Toole, he is something of a walking orchestra, and there are no timbres he does not strike as he wheedles, cajoles, bullies, supplicates, threatens, and finally embraces his alienated wife and her children.

The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), written by James Goldman from his stage play of the same name, with Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, Anthony Hopkins, John Castle, Nigel Terry, and Timothy Dalton. One must appreciate Beethoven to grasp the powers of this film, which reside principally in ensemble performance. O’Toole, as an English king visiting France and spending Easter with his stubborn and brilliantly contentious wife (Hepburn) and three sons (Hopkins, Castle, Terry), glows with vituperation, whines with loneliness, grimaces with intent, and fails in grand spectacular fashion to decide which of the pathetic offspring will wear his crown when he is dead. The serpentine French monarch Philippe (Dalton), visiting in order to light as many fuses as possible, does nothing to help the situation. For devotées of screen acting, it is a lesson to watch the young Hopkins, the young (and brilliantly polished) Castle, and the young Terry (who would play King Arthur for John Boorman in Excalibur) dash and pose in the shadows of the great Hepburn and the great O’Toole; every day on the set was an education for them, no doubt. Hepburn’s Parkinson’s is occasionally evident, a pointer to the fact that she worked against huge odds to bring off this stellar performance with its continual reversals and complex contradictions: she adores Henry, but she will do anything to destroy him. As for O’Toole, he is something of a walking orchestra, and there are no timbres he does not strike as he wheedles, cajoles, bullies, supplicates, threatens, and finally embraces his alienated wife and her children.

The shock in this film for those who have seen Timothy Dalton’s later performances–which seem never to fail in their display of unctuousness or smarmy conceit–is a view of the enormous range and delicacy of which he was capable before filmmaking ruined him. His work in this film is a marvel, and when he is onscreen one cannot afford to blink for fear of missing a tiny flicker in the cheek, an even tinier posture of the mouth. One of the truly crafted performances in the history of the British screen.

*

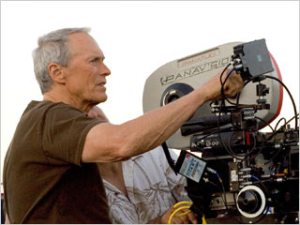

Changeling (Clint Eastwood, 2008), with Angelina Jolie and John Malkovich. In 1920s Los Angeles, the mother of a 10-year-old boy comes home from work one day to find him gone. Agonized, she contacts the LAPD, a bed of corruption. They do virtually nothing to help, but weeks later the announcement is made that the boy has been found and is being returned to her by train. She goes to the station, surrounded by press and officials of the force, eager and ready to put the horros of the recent past behind her. When the boy gets off the train, she is convinced he is not her son. He says he is, and moves in with her, but she continues to press the police, now in the face of an actual child whose presence compromises her efforts to raise public consciousness to the fact that the actual son is still missing.

Changeling (Clint Eastwood, 2008), with Angelina Jolie and John Malkovich. In 1920s Los Angeles, the mother of a 10-year-old boy comes home from work one day to find him gone. Agonized, she contacts the LAPD, a bed of corruption. They do virtually nothing to help, but weeks later the announcement is made that the boy has been found and is being returned to her by train. She goes to the station, surrounded by press and officials of the force, eager and ready to put the horros of the recent past behind her. When the boy gets off the train, she is convinced he is not her son. He says he is, and moves in with her, but she continues to press the police, now in the face of an actual child whose presence compromises her efforts to raise public consciousness to the fact that the actual son is still missing.

The story becomes far more interesting, complicated, revolting, and sad, and potential viewers should be ready to be exposed to scenes of dramatically necessary but nevertheless disturbing violence, both physical and psychological. The pacing and direction by Eastwood, especially as directed toward a climactic point when Jolie is put into doubt about the identity of the boy who is living with her, are more than brilliant–they give clear evidence that this is a filmmaker of the keenest and most musical sensibilities at work with material that is haunting and beautiful. Malkovich has–for once–allowed his character to come to prominence. All the supporting players are perfectly cast, especially Devon Conti as the boy who comes by train, Michael Kelly as the only detective in LA willing to try to help, Peter Gerety as a sleazy doctor working with the police, and Colm Feore as the Chief who is well past his usefulness. Deeply frightening.

*

Revolutionary Road (Sam Mendes, 2008), with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kathy Bates. A young couple in the suburbs, with the husband training into New York à la The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and the wife going slowly mad in her chokingly feminine domestic world. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique come to life. The marital stress might have been more convincing with other performers; these two, who can both be convincing, haven’t found the right material here, and Mendes’s penchant for theatrical staging keeps forcing him to set up situations for their rise and fall but without regard for truths the eye can see. Leonardo just doesn’t look old or worn enough, and his voice, as he screams again and again, keeps breaking up. The story points couldn’t be more conventional, and the depiction of the 1950s is as flawed as it was in Todd Haynes’s over-sung Far From Heaven. The film is saved–just–by a too-brief appearance of Michael Shannon in the role of a neighbor’s socially and psychologically maladjusted son: he’s no toddler, but looms almost seven feet tall, an incarnation of the giant Diane Arbus photographed, with a far too extroverted sense of social propriety and a gaze that is discomfortingly straight. Shannon appeared, too briefly again, in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, as the heroic cop who finds the survivors; here he puts DiCaprio and even the hard-working Winslet out of their league.

Revolutionary Road (Sam Mendes, 2008), with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kathy Bates. A young couple in the suburbs, with the husband training into New York à la The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and the wife going slowly mad in her chokingly feminine domestic world. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique come to life. The marital stress might have been more convincing with other performers; these two, who can both be convincing, haven’t found the right material here, and Mendes’s penchant for theatrical staging keeps forcing him to set up situations for their rise and fall but without regard for truths the eye can see. Leonardo just doesn’t look old or worn enough, and his voice, as he screams again and again, keeps breaking up. The story points couldn’t be more conventional, and the depiction of the 1950s is as flawed as it was in Todd Haynes’s over-sung Far From Heaven. The film is saved–just–by a too-brief appearance of Michael Shannon in the role of a neighbor’s socially and psychologically maladjusted son: he’s no toddler, but looms almost seven feet tall, an incarnation of the giant Diane Arbus photographed, with a far too extroverted sense of social propriety and a gaze that is discomfortingly straight. Shannon appeared, too briefly again, in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, as the heroic cop who finds the survivors; here he puts DiCaprio and even the hard-working Winslet out of their league.

*

Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008), from his stageplay, with Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis. A Catholic elementary school in Boston, c. 1965. The friendly priest is detested by the principal, who doesn’t like his strategies for opening the Church to the modern age. When at one point it seems he has been a little too friendly and protective to a black child, she makes it her purpose in life to reveal him as a reprobate whose morality has been corrupted. Finally, threatening him with his past, she succeeds in forcing his resignation, it becoming clear only later, as she confides to a young nun, that she never really did investigate him at all, only claimed she would–and his resignation is therefore proof of his guilt. A fascinating enough proposition, focussing on the importance of doubt in our moral evaluation of one another: ultimately the film resides less in the doubt than in the awkward and beautiful chemistry between Streep and Hoffman. He turns in a competent, and modest, performance while she goes a step beyond The Devil Wears Prada to construct an icon of moral certainty and hellish conviction. If Streep has too often over the years punctured her performances by drawing overt attention to her technical strengths, here she holds herself under, and inside, the role all through, so that the character becomes one of the great figurations of cinema. A cat self-purposed to catch its mouse, we know from the start that she will have him, but not quite how. Shanley has a fine ear for language and for feeling; but he doesn’t compose with a filmmaker’s eye.

Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008), from his stageplay, with Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis. A Catholic elementary school in Boston, c. 1965. The friendly priest is detested by the principal, who doesn’t like his strategies for opening the Church to the modern age. When at one point it seems he has been a little too friendly and protective to a black child, she makes it her purpose in life to reveal him as a reprobate whose morality has been corrupted. Finally, threatening him with his past, she succeeds in forcing his resignation, it becoming clear only later, as she confides to a young nun, that she never really did investigate him at all, only claimed she would–and his resignation is therefore proof of his guilt. A fascinating enough proposition, focussing on the importance of doubt in our moral evaluation of one another: ultimately the film resides less in the doubt than in the awkward and beautiful chemistry between Streep and Hoffman. He turns in a competent, and modest, performance while she goes a step beyond The Devil Wears Prada to construct an icon of moral certainty and hellish conviction. If Streep has too often over the years punctured her performances by drawing overt attention to her technical strengths, here she holds herself under, and inside, the role all through, so that the character becomes one of the great figurations of cinema. A cat self-purposed to catch its mouse, we know from the start that she will have him, but not quite how. Shanley has a fine ear for language and for feeling; but he doesn’t compose with a filmmaker’s eye.

*

Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008), with Sean Penn, Emile Hirsch, Josh Brolin, Diego Pena, Victor Garber, and James Franco. At once, one of the supreme performances of Sean Penn’s career–delicate, playful, sincere, convicted, urgent–and another of those Gus Van Sant fiddlings with homoerotic experience, in which all the elements come properly gift-wrapped but some dark shame or embarrassment prevents the filmmaker from showing, in plain light, what all the fuss is about. One senses here the importance, historically, of the Castro district gay scene in 1970s San Francisco, and one is confronted with a huge array of extremely energetic and well-meaning young characters thrown together by a conviction that the gay experience should be as open and free as any other in modern America. But that experience–which is shown to mobilize all sorts of political and personal resentments and to erect all sorts of obstacles in this film–is itself kept largely off the screen, excepting a few passionate kisses and a large number of “knowing” glances. Like Brokeback Mountain, ostensibly about gay life in the 1960s, Milk remains in a kind of closet, where Harvey Milk can beckon his boyfriend laughingly to wear the tighest jeans possible when he comes to visit at City Hall yet at the same time never try to touch those jeans on camera. Who, one has to wonder, is the audience this film is aimed at; and why must that audience still continue to repress creative artists like Van Sant so that they must only whisper their home truths?

Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008), with Sean Penn, Emile Hirsch, Josh Brolin, Diego Pena, Victor Garber, and James Franco. At once, one of the supreme performances of Sean Penn’s career–delicate, playful, sincere, convicted, urgent–and another of those Gus Van Sant fiddlings with homoerotic experience, in which all the elements come properly gift-wrapped but some dark shame or embarrassment prevents the filmmaker from showing, in plain light, what all the fuss is about. One senses here the importance, historically, of the Castro district gay scene in 1970s San Francisco, and one is confronted with a huge array of extremely energetic and well-meaning young characters thrown together by a conviction that the gay experience should be as open and free as any other in modern America. But that experience–which is shown to mobilize all sorts of political and personal resentments and to erect all sorts of obstacles in this film–is itself kept largely off the screen, excepting a few passionate kisses and a large number of “knowing” glances. Like Brokeback Mountain, ostensibly about gay life in the 1960s, Milk remains in a kind of closet, where Harvey Milk can beckon his boyfriend laughingly to wear the tighest jeans possible when he comes to visit at City Hall yet at the same time never try to touch those jeans on camera. Who, one has to wonder, is the audience this film is aimed at; and why must that audience still continue to repress creative artists like Van Sant so that they must only whisper their home truths?

Aside from one brief shot of Penn and Pena rolling naked on a shadowy floor, there is nothing here offensive to the bourgeois homophobic audience; and indeed the most profoundly offensive imagery consists in the tv closeups of Anita Bryant as she campaigns to eradicate homosexuality from America.

Penn, meanwhile, is galvanizing, and shows that he is the most under-rated actor in America.

*

Cherryblossoms – Hanami (Dorrie Dörrie, 2008), with Elmar Wepper, Hannelore Elsner, Aya Irizuki, Maximilian Brückner. In a small town in the German Alps, an aging public worker has been diagnosed with a terminal disease and only his wife knows. She persuades him that they should visit the children in Berlin, which they do in a lengthy sequence delicious for its squeamish discomforts: the children care little for the realities of their parents’ lives, and act purely out of propriety in hosting them. The man and his wife go off to the Black Sea, where they meditate on their future, and he talks of how he would like his ashes disposed of (still ignorant of his condition). Suddenly, however, the wife dies in the night. Now, to try to live out the life she could not live, the old man takes himself off to visit his second son, who lives in Tokyo. This son, too, has no time for him, and leaves him alone all day. He wanders, and meets a young dancer whose mother has died. They become friends. She accompanies him on a pilgrimage to the place his wife had most wanted to see, Mount Fuji.

Cherryblossoms – Hanami (Dorrie Dörrie, 2008), with Elmar Wepper, Hannelore Elsner, Aya Irizuki, Maximilian Brückner. In a small town in the German Alps, an aging public worker has been diagnosed with a terminal disease and only his wife knows. She persuades him that they should visit the children in Berlin, which they do in a lengthy sequence delicious for its squeamish discomforts: the children care little for the realities of their parents’ lives, and act purely out of propriety in hosting them. The man and his wife go off to the Black Sea, where they meditate on their future, and he talks of how he would like his ashes disposed of (still ignorant of his condition). Suddenly, however, the wife dies in the night. Now, to try to live out the life she could not live, the old man takes himself off to visit his second son, who lives in Tokyo. This son, too, has no time for him, and leaves him alone all day. He wanders, and meets a young dancer whose mother has died. They become friends. She accompanies him on a pilgrimage to the place his wife had most wanted to see, Mount Fuji.

A touching and observant film, somewhat in the style of Ingmar Bergman’s The Touch. Elegant cinematography of Berlin and especially of Tokyo and Fujiyama by Hanno Lentz. And remarkable performances of polite family disunity, in which it becomes pungently apparent that not only can children cease to understand or care about their parents, parents can cease to understand their children. The little Japanese girl’s occupation is a dance beside a busy canal, where, dressed in kimono, she twists around the coils of a pink telephone wire, holding the receiver to her ear and trying to speak or hear across the abyss: this recurring image beautifully addresses the many chasms that have opened between the characters here, and their continuing hopes to cross them by way of some special attention, some special intensification of concern.

The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), written by James Goldman from his stage play of the same name, with Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, Anthony Hopkins, John Castle, Nigel Terry, and Timothy Dalton. One must appreciate Beethoven to grasp the powers of this film, which reside principally in ensemble performance. O’Toole, as an English king visiting France and spending Easter with his stubborn and brilliantly contentious wife (Hepburn) and three sons (Hopkins, Castle, Terry), glows with vituperation, whines with loneliness, grimaces with intent, and fails in grand spectacular fashion to decide which of the pathetic offspring will wear his crown when he is dead. The serpentine French monarch Philippe (Dalton), visiting in order to light as many fuses as possible, does nothing to help the situation. For devotées of screen acting, it is a lesson to watch the young Hopkins, the young (and brilliantly polished) Castle, and the young Terry (who would play King Arthur for John Boorman in Excalibur) dash and pose in the shadows of the great Hepburn and the great O’Toole; every day on the set was an education for them, no doubt. Hepburn’s Parkinson’s is occasionally evident, a pointer to the fact that she worked against huge odds to bring off this stellar performance with its continual reversals and complex contradictions: she adores Henry, but she will do anything to destroy him. As for O’Toole, he is something of a walking orchestra, and there are no timbres he does not strike as he wheedles, cajoles, bullies, supplicates, threatens, and finally embraces his alienated wife and her children.

The Lion in Winter (Anthony Harvey, 1968), written by James Goldman from his stage play of the same name, with Peter O’Toole, Katharine Hepburn, Anthony Hopkins, John Castle, Nigel Terry, and Timothy Dalton. One must appreciate Beethoven to grasp the powers of this film, which reside principally in ensemble performance. O’Toole, as an English king visiting France and spending Easter with his stubborn and brilliantly contentious wife (Hepburn) and three sons (Hopkins, Castle, Terry), glows with vituperation, whines with loneliness, grimaces with intent, and fails in grand spectacular fashion to decide which of the pathetic offspring will wear his crown when he is dead. The serpentine French monarch Philippe (Dalton), visiting in order to light as many fuses as possible, does nothing to help the situation. For devotées of screen acting, it is a lesson to watch the young Hopkins, the young (and brilliantly polished) Castle, and the young Terry (who would play King Arthur for John Boorman in Excalibur) dash and pose in the shadows of the great Hepburn and the great O’Toole; every day on the set was an education for them, no doubt. Hepburn’s Parkinson’s is occasionally evident, a pointer to the fact that she worked against huge odds to bring off this stellar performance with its continual reversals and complex contradictions: she adores Henry, but she will do anything to destroy him. As for O’Toole, he is something of a walking orchestra, and there are no timbres he does not strike as he wheedles, cajoles, bullies, supplicates, threatens, and finally embraces his alienated wife and her children. Changeling (Clint Eastwood, 2008), with Angelina Jolie and John Malkovich. In 1920s Los Angeles, the mother of a 10-year-old boy comes home from work one day to find him gone. Agonized, she contacts the LAPD, a bed of corruption. They do virtually nothing to help, but weeks later the announcement is made that the boy has been found and is being returned to her by train. She goes to the station, surrounded by press and officials of the force, eager and ready to put the horros of the recent past behind her. When the boy gets off the train, she is convinced he is not her son. He says he is, and moves in with her, but she continues to press the police, now in the face of an actual child whose presence compromises her efforts to raise public consciousness to the fact that the actual son is still missing.

Changeling (Clint Eastwood, 2008), with Angelina Jolie and John Malkovich. In 1920s Los Angeles, the mother of a 10-year-old boy comes home from work one day to find him gone. Agonized, she contacts the LAPD, a bed of corruption. They do virtually nothing to help, but weeks later the announcement is made that the boy has been found and is being returned to her by train. She goes to the station, surrounded by press and officials of the force, eager and ready to put the horros of the recent past behind her. When the boy gets off the train, she is convinced he is not her son. He says he is, and moves in with her, but she continues to press the police, now in the face of an actual child whose presence compromises her efforts to raise public consciousness to the fact that the actual son is still missing. Revolutionary Road (Sam Mendes, 2008), with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kathy Bates. A young couple in the suburbs, with the husband training into New York à la The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and the wife going slowly mad in her chokingly feminine domestic world. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique come to life. The marital stress might have been more convincing with other performers; these two, who can both be convincing, haven’t found the right material here, and Mendes’s penchant for theatrical staging keeps forcing him to set up situations for their rise and fall but without regard for truths the eye can see. Leonardo just doesn’t look old or worn enough, and his voice, as he screams again and again, keeps breaking up. The story points couldn’t be more conventional, and the depiction of the 1950s is as flawed as it was in Todd Haynes’s over-sung Far From Heaven. The film is saved–just–by a too-brief appearance of Michael Shannon in the role of a neighbor’s socially and psychologically maladjusted son: he’s no toddler, but looms almost seven feet tall, an incarnation of the giant Diane Arbus photographed, with a far too extroverted sense of social propriety and a gaze that is discomfortingly straight. Shannon appeared, too briefly again, in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, as the heroic cop who finds the survivors; here he puts DiCaprio and even the hard-working Winslet out of their league.

Revolutionary Road (Sam Mendes, 2008), with Kate Winslet, Leonardo DiCaprio, Kathy Bates. A young couple in the suburbs, with the husband training into New York à la The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and the wife going slowly mad in her chokingly feminine domestic world. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique come to life. The marital stress might have been more convincing with other performers; these two, who can both be convincing, haven’t found the right material here, and Mendes’s penchant for theatrical staging keeps forcing him to set up situations for their rise and fall but without regard for truths the eye can see. Leonardo just doesn’t look old or worn enough, and his voice, as he screams again and again, keeps breaking up. The story points couldn’t be more conventional, and the depiction of the 1950s is as flawed as it was in Todd Haynes’s over-sung Far From Heaven. The film is saved–just–by a too-brief appearance of Michael Shannon in the role of a neighbor’s socially and psychologically maladjusted son: he’s no toddler, but looms almost seven feet tall, an incarnation of the giant Diane Arbus photographed, with a far too extroverted sense of social propriety and a gaze that is discomfortingly straight. Shannon appeared, too briefly again, in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, as the heroic cop who finds the survivors; here he puts DiCaprio and even the hard-working Winslet out of their league. Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008), from his stageplay, with Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis. A Catholic elementary school in Boston, c. 1965. The friendly priest is detested by the principal, who doesn’t like his strategies for opening the Church to the modern age. When at one point it seems he has been a little too friendly and protective to a black child, she makes it her purpose in life to reveal him as a reprobate whose morality has been corrupted. Finally, threatening him with his past, she succeeds in forcing his resignation, it becoming clear only later, as she confides to a young nun, that she never really did investigate him at all, only claimed she would–and his resignation is therefore proof of his guilt. A fascinating enough proposition, focussing on the importance of doubt in our moral evaluation of one another: ultimately the film resides less in the doubt than in the awkward and beautiful chemistry between Streep and Hoffman. He turns in a competent, and modest, performance while she goes a step beyond The Devil Wears Prada to construct an icon of moral certainty and hellish conviction. If Streep has too often over the years punctured her performances by drawing overt attention to her technical strengths, here she holds herself under, and inside, the role all through, so that the character becomes one of the great figurations of cinema. A cat self-purposed to catch its mouse, we know from the start that she will have him, but not quite how. Shanley has a fine ear for language and for feeling; but he doesn’t compose with a filmmaker’s eye.

Doubt (John Patrick Shanley, 2008), from his stageplay, with Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, and Viola Davis. A Catholic elementary school in Boston, c. 1965. The friendly priest is detested by the principal, who doesn’t like his strategies for opening the Church to the modern age. When at one point it seems he has been a little too friendly and protective to a black child, she makes it her purpose in life to reveal him as a reprobate whose morality has been corrupted. Finally, threatening him with his past, she succeeds in forcing his resignation, it becoming clear only later, as she confides to a young nun, that she never really did investigate him at all, only claimed she would–and his resignation is therefore proof of his guilt. A fascinating enough proposition, focussing on the importance of doubt in our moral evaluation of one another: ultimately the film resides less in the doubt than in the awkward and beautiful chemistry between Streep and Hoffman. He turns in a competent, and modest, performance while she goes a step beyond The Devil Wears Prada to construct an icon of moral certainty and hellish conviction. If Streep has too often over the years punctured her performances by drawing overt attention to her technical strengths, here she holds herself under, and inside, the role all through, so that the character becomes one of the great figurations of cinema. A cat self-purposed to catch its mouse, we know from the start that she will have him, but not quite how. Shanley has a fine ear for language and for feeling; but he doesn’t compose with a filmmaker’s eye. Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008), with Sean Penn, Emile Hirsch, Josh Brolin, Diego Pena, Victor Garber, and James Franco. At once, one of the supreme performances of Sean Penn’s career–delicate, playful, sincere, convicted, urgent–and another of those Gus Van Sant fiddlings with homoerotic experience, in which all the elements come properly gift-wrapped but some dark shame or embarrassment prevents the filmmaker from showing, in plain light, what all the fuss is about. One senses here the importance, historically, of the Castro district gay scene in 1970s San Francisco, and one is confronted with a huge array of extremely energetic and well-meaning young characters thrown together by a conviction that the gay experience should be as open and free as any other in modern America. But that experience–which is shown to mobilize all sorts of political and personal resentments and to erect all sorts of obstacles in this film–is itself kept largely off the screen, excepting a few passionate kisses and a large number of “knowing” glances. Like Brokeback Mountain, ostensibly about gay life in the 1960s, Milk remains in a kind of closet, where Harvey Milk can beckon his boyfriend laughingly to wear the tighest jeans possible when he comes to visit at City Hall yet at the same time never try to touch those jeans on camera. Who, one has to wonder, is the audience this film is aimed at; and why must that audience still continue to repress creative artists like Van Sant so that they must only whisper their home truths?

Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008), with Sean Penn, Emile Hirsch, Josh Brolin, Diego Pena, Victor Garber, and James Franco. At once, one of the supreme performances of Sean Penn’s career–delicate, playful, sincere, convicted, urgent–and another of those Gus Van Sant fiddlings with homoerotic experience, in which all the elements come properly gift-wrapped but some dark shame or embarrassment prevents the filmmaker from showing, in plain light, what all the fuss is about. One senses here the importance, historically, of the Castro district gay scene in 1970s San Francisco, and one is confronted with a huge array of extremely energetic and well-meaning young characters thrown together by a conviction that the gay experience should be as open and free as any other in modern America. But that experience–which is shown to mobilize all sorts of political and personal resentments and to erect all sorts of obstacles in this film–is itself kept largely off the screen, excepting a few passionate kisses and a large number of “knowing” glances. Like Brokeback Mountain, ostensibly about gay life in the 1960s, Milk remains in a kind of closet, where Harvey Milk can beckon his boyfriend laughingly to wear the tighest jeans possible when he comes to visit at City Hall yet at the same time never try to touch those jeans on camera. Who, one has to wonder, is the audience this film is aimed at; and why must that audience still continue to repress creative artists like Van Sant so that they must only whisper their home truths? Cherryblossoms – Hanami (Dorrie Dörrie, 2008), with Elmar Wepper, Hannelore Elsner, Aya Irizuki, Maximilian Brückner. In a small town in the German Alps, an aging public worker has been diagnosed with a terminal disease and only his wife knows. She persuades him that they should visit the children in Berlin, which they do in a lengthy sequence delicious for its squeamish discomforts: the children care little for the realities of their parents’ lives, and act purely out of propriety in hosting them. The man and his wife go off to the Black Sea, where they meditate on their future, and he talks of how he would like his ashes disposed of (still ignorant of his condition). Suddenly, however, the wife dies in the night. Now, to try to live out the life she could not live, the old man takes himself off to visit his second son, who lives in Tokyo. This son, too, has no time for him, and leaves him alone all day. He wanders, and meets a young dancer whose mother has died. They become friends. She accompanies him on a pilgrimage to the place his wife had most wanted to see, Mount Fuji.

Cherryblossoms – Hanami (Dorrie Dörrie, 2008), with Elmar Wepper, Hannelore Elsner, Aya Irizuki, Maximilian Brückner. In a small town in the German Alps, an aging public worker has been diagnosed with a terminal disease and only his wife knows. She persuades him that they should visit the children in Berlin, which they do in a lengthy sequence delicious for its squeamish discomforts: the children care little for the realities of their parents’ lives, and act purely out of propriety in hosting them. The man and his wife go off to the Black Sea, where they meditate on their future, and he talks of how he would like his ashes disposed of (still ignorant of his condition). Suddenly, however, the wife dies in the night. Now, to try to live out the life she could not live, the old man takes himself off to visit his second son, who lives in Tokyo. This son, too, has no time for him, and leaves him alone all day. He wanders, and meets a young dancer whose mother has died. They become friends. She accompanies him on a pilgrimage to the place his wife had most wanted to see, Mount Fuji.

An Audience Is An Audience

5 09 2008Sadly, an audience is an audience. Overheard last night, at the opening gala of the Toronto International Film Festival, from a twentysomething woman responding to the words “Burt Bacharach” that were floating in the air near her ears: “Oh yeah, I know him. I know him! He’s the guy who plays two pianos. He plays two pianos! He was in Austin Powers, and he played two pianos!” And she is, of course, correct.

This is the gentleman who was companion in his youth to Marlene Dietrich. This is the gentleman who wrote “A House Is Not a Home,” and “Do You Know the Way to San Jose” and “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” and “This Guy’s In Love With You,” and “The Look of Love,” and “What’s New Pussycat?” and so much else. Now he’s the man who plays two pianos in Austin Powers. This is the man upon whose songs Dionne Warwick made her career—-and now . . .

Well, he has an audience, and an audience is an audience.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: Austin Powers, Burt Bacharach, Dionne Warwick, history of popular culture, TIFF08, Toronto International Film Festival

Categories : Cultural comment